Introduction

Kyushu

Kagoshima

Kumamoto

Nagasaki

Saga

Fukuoka

Southwestern Honshu

Yamaguchi

Shimane

Northwestern Honshu

Ishikawa

Toyama

Niigata

Yamagata Pref.

Western Hokkaido

Conclusion

Introduction

Islands as well as peninsula are often fringed with rocky coasts where water motion is enough for macroalgae to lush (Tokuda et al. 1994, Fujita et al. 2010, Fisheries Agency 2021). Macroalgae are important primary producers in shallow waters including foundation species (Dayton 1972) which support fish and shellfish by providing habitat, nursery, shelter and food (Japan Fisheries Resource Conservation Association 1984, Shoji 2009). Some macrolalgal species are used as human food (e.g., salads, soup stock and ingredients) or as a resource of hydocolloids such as agar (Miyashita 1974, Imada 2003, Ohno 2004, Mauritsen 2013).

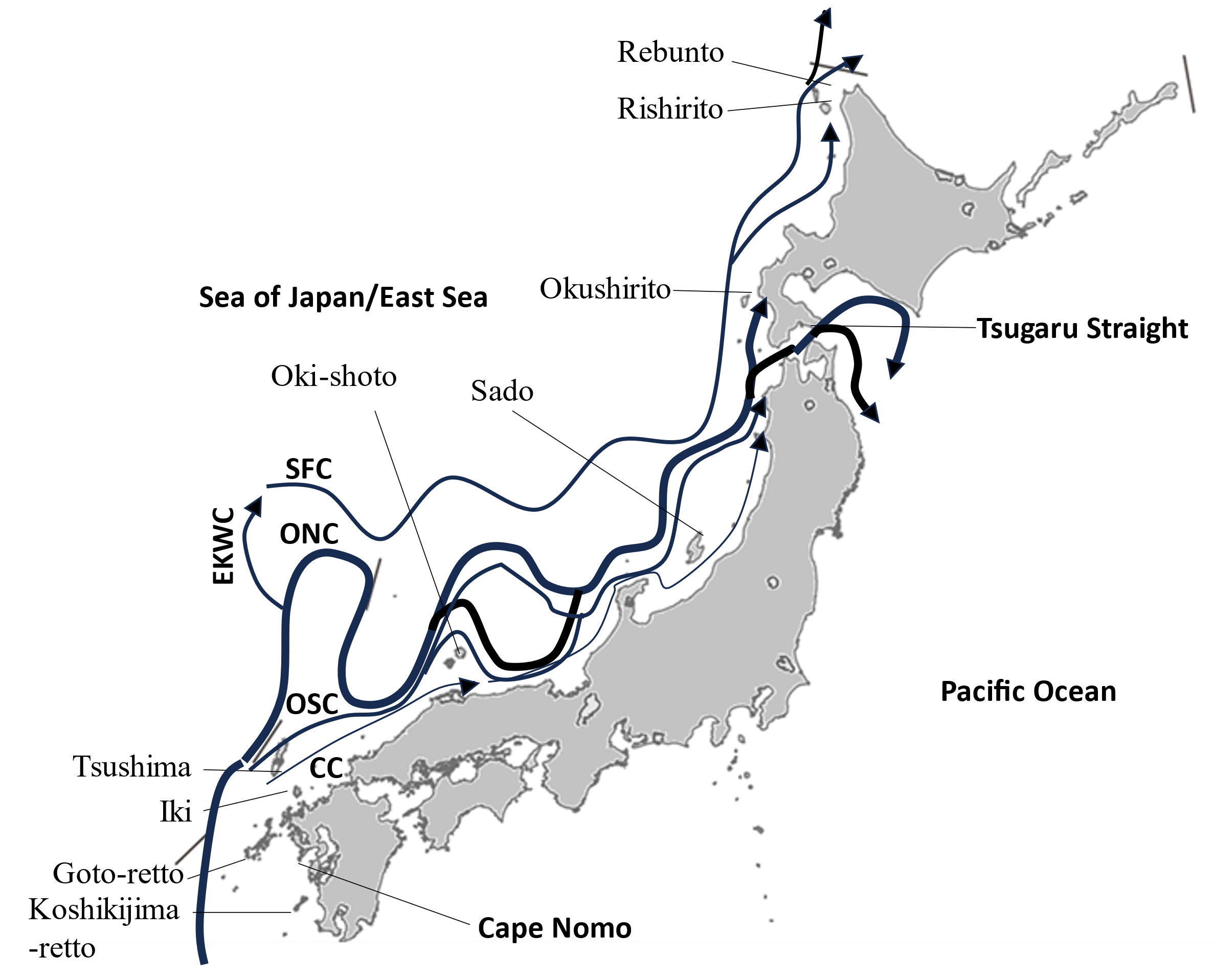

Japan is geographically distributed from subtropical (south) to cold temperate region and the marine macroalgal diversity is very high with 1,693 species (Suzuki 2024). The country is comprised of 14,125 islands (> 0.1 km around); among the 421 populated islands, 146 islands (Table 1, Suppl. Table S1) are located on the western coasts of Japan from Kyushu to Hokkaido along the Tsushima Warm Current (TWC) (Fig. 1). This is the longest line of islands around Japan dominated by a single sea current, which includes important islands from the view point of algal flora (Okamura 1936, Noda 1987, Suzuki 2024), harvest of commercial algae (e.g., Inoue 1949, Miyabe 1957), food culture (Imada 2003, Ohno 2004) and human interaction with the neighboring countries (e.g., Innami 2011).

Some areas in these islands were registered as marine parks after 1970s (Marine Parks Center of Japan 1975); ‘marine park areas’ were designated with their surrounding ‘ordinary areas (area 1 km off from shore line)’ for preserving beautiful undersea-scape (Suppl. Table S1). Preliminary studies in these marine park candidates are the valuable records of algal beds (i.e. flora, fauna, environmental conditions, color image of seascape) in 1960’s (Kumamoto Pref. 1968, Niigata Pref. 1969) or 1970’s (Nagasaki Pref. 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, Saga Pref. 1970) though the field surveys were largely limited to summer season.

Table 1.

Number, area, population and major populated islands of each prefecture in Japan, ordered from south to north (See Suppl. Table S1 for the details)

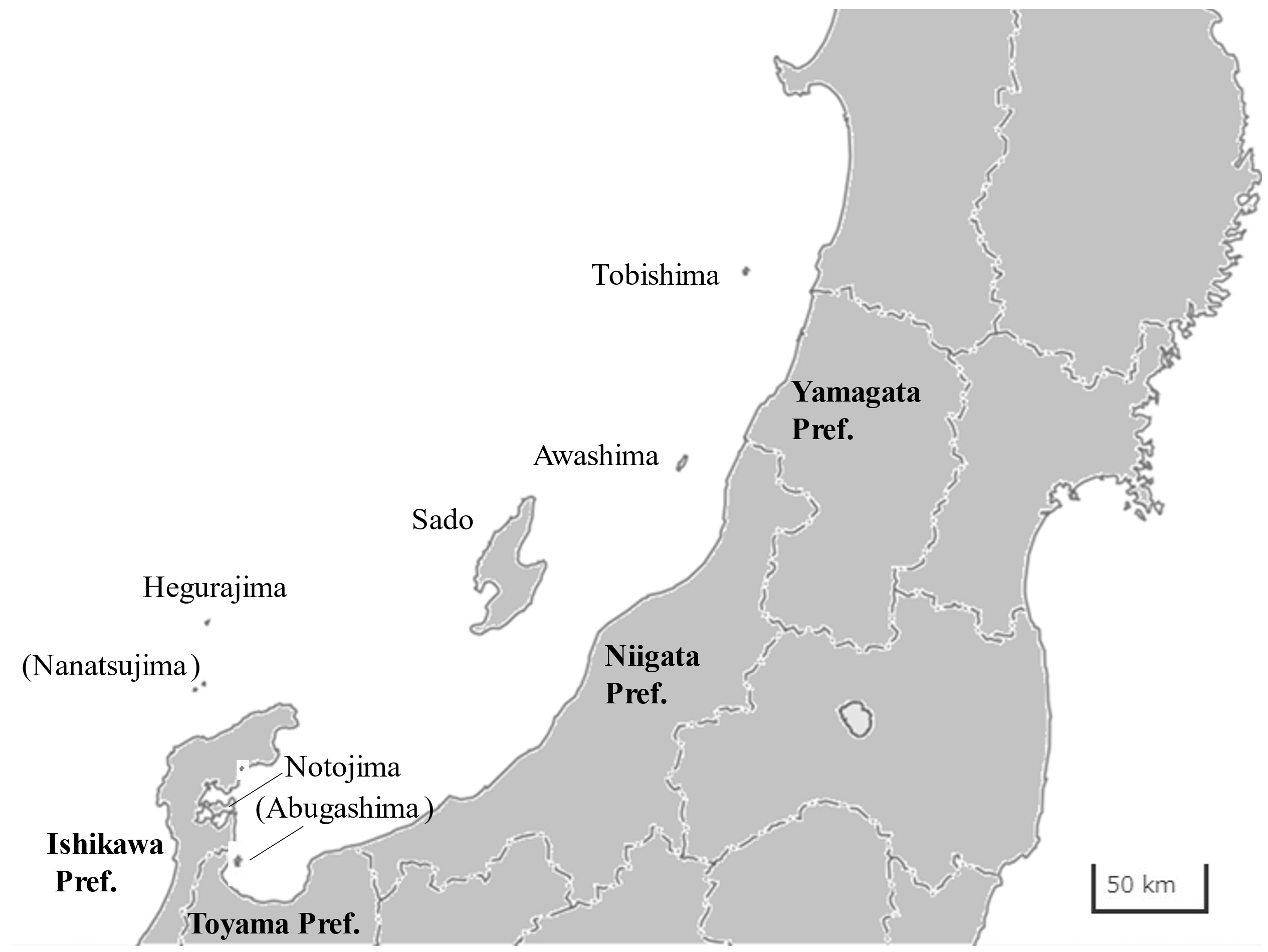

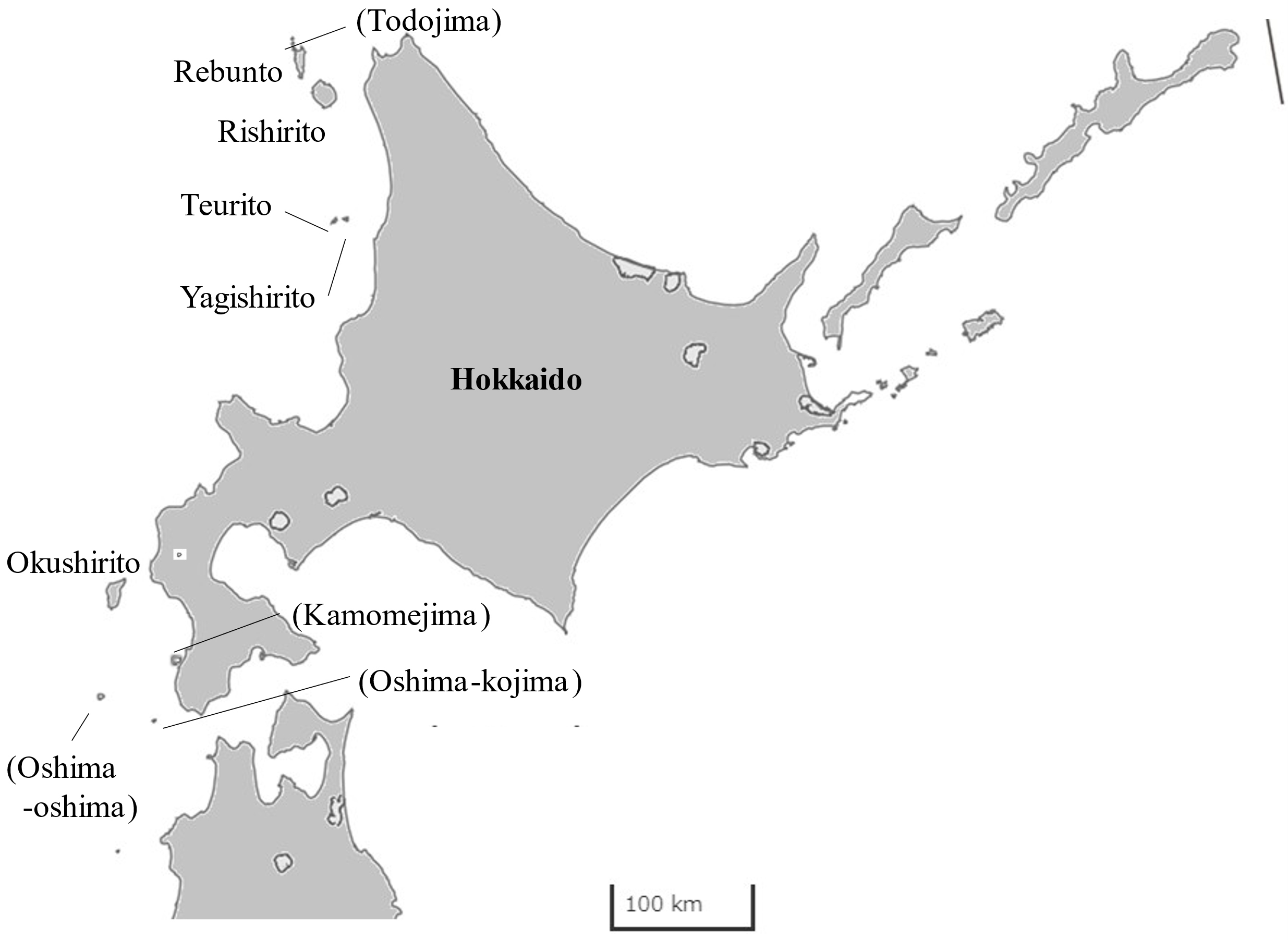

Fig. 1.

Schematic of Tsushima Warm Current (TWC) systems after Yabe et al. (2021) and Ichikawa and Beardsley (2002) for the stem of the current in the south of Tsushima. CC: Coastal Current; EKWC: East Korean Warm Current; ONC: Offshore North Current; OSC: Offshore South Current; SFC: Subpolar Front Current.

In addition, most of western islands are identified as ‘ecologically or biologically significant marine areas’ (EBSAs) (Suppl. Table S1) due to their high biodiversity since 2011 (Nature Conservation Bureau 2016). In MPs and EBSAs, developmental activities (e.g., construction, fishery, mining) cannot be conducted without permission of the designators of these parks.

The Environmental Agency (reorganized into Ministry of the Environment in 2001) conducted nation-wide surveys of algal beds in 1978, 1989-93, 1997-2003 and 2018-21. Among these data, only first two surveys conducted in the same regime (purpose, depth range, method) are comparable; the most detailed algal bed data of islands are provided in Nature Conservation Bureau and Marine Parks Center of Japan (1994).

As western islands are influenced by TWC, which is increasing throughflow transport trend (Kida et al. 2021) and causing elevation of water temperature (Japan Meteorological Agency 2024), increase rates (from 1900 to 2022, °C per century) of area-averaged annual mean sea-surface temperature) are 1.29°C in western Kyushu, 1.47°C in southwestern Honshu, 1.87°C in northwestern Honshu and 0.88°C in western Hokkaido. The recent deforestation of algal bed and replacement of dominant canopy species (from kelp to Sargassum and corals) are highly due to the elevation of water temperature and the related activation of herbivores and sometimes directly by stressing algal thalli (Fujita et al. 2006b, 2008, 2010, Kumagai et al. 2018, Fisheries Agency 2021).

In this difficult conditions, maintenance and restoration of algal beds have been challenged in many western islands as well as other parts of Japan (Fujita et al. 2006b, 2008, 2010, Fisheries Agency 2021). Such activities have been supported by subsidies from Fisheries Agency to revitalize fisheries in remote islands (Remote Island Grants, RIG) since 2005 or to promote the Environment and Ecosystem Protection Project (EEPP, 2009-12) and the succeeding Fisheries Multiple functions Demonstration Project (FMDP, 2013-). As the purpose and results of RIG are not strictly limited, contents of activities are neither compiled nor publicized. However, results of FMDP are reported in annual meeting (oral or poster presentation, at frequency of a few topics/year) on webpage (https//hitoumi jp./torikumi) which is managed by National Federation of Fisheries Cooperatives. FMDP is promoted by local activity groups comprised of fishermen including supporter, researchers and volunteers). The groups have to contract with city/town/village; the budget (nation:1/2, prefecture:1/2, city/town/village:1/2) is allocated through a local committee in each prefecture (Sekine 2015).

In the present review, information on algal flora, vegetational status, commercial algal resources, and recent status and restoration of algal beds in the western islands of Japan were reported. Information of each prefecture was described from south to north according to the direction of the flow of TWC as the order surely makes it easy to image the influence of the warm current. Source of information includes scientific papers, commercial journals, public reports and homepage of projects, local guide books and municipal history books. Here, ‘island(s)’ or ‘isl(s).’was not added to the name of each island for shortening because island name in Japanese language usually includes suffix (-shima, jima or -to) meaning island, and name of island group includes shoto’, ‘retto’ or ‘gunto’. However, these suffices were not added to the three larger islands, Tsushima (meaning paired horses, but not island in the last part of the name), Iki and Sado, following custom. Furthermore, latest names of marine algae were used instead of names originally used in the literature. For example, Meristotheca japonica is used for M. papulosa according to Yang et al. (2024).

Location of major islands and smaller islands in Kyushu are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and Suppl. Fig. S2, Suppl. Fig. S3, Suppl. Fig. S4, Suppl. Fig. S5, respectively. Suppl. Table S1 includes data of all western islands and some non-populated islands: area, population, connectivity with mainland or other island, designation of (quasi-) NP and registered number of EBSA. Area and population data were cited from Center for Research and Promotion of Japanese Islands (2023).

Among the 146 populated islands, 82% are in Kyushu; 49% belong to Nagasaki Prefecture (Table 1). In area, islands <1 km2, 1-10 km2, 10-100 km2 and > 100 km2 share 38%, 38%, 16% and 8%, respectively. Most of the smaller populated islands are located in western Kyushu. In population, islands with <10, 10-100, 100-1000, 1000-10,000, >10,000 (people) share 10%, 23%, 42%, 17%, 8%, respectively, though no data were available (combined with nearby islands) on some islands. Comparing with the data a decade ago, population decreased in 94% of the western islands; total population of the western islands are 398,368 persons in 2020 after decreasing 13.9% from 2010.

In Table 2, macroalgae described as new species from western islands and currently accepted taxonomically are listed with their type localities. In Table 3, algal resources (mainly as food) of selected islands are listed using the data in local guide books. In Table 4, distributions of destructive herbivores (3 sea urchins and 4 herbivorous fishes) are summarized using the data in Fujita et al. (2006b, 2008) and Fisheries Agency (2021). In Table 5, contents of FDMP activities practiced in western islands are listed. The following is outline of information on each prefecture.

Table 2.

Latest names of macroalgae described from western islands, Japan, which are currently accepted taxonomically

| Prefecture | Species* | Type locality |

| Kagoshima | Hypnea yamadae Tak. Tanaka | Uji-gunto |

| Akalaphycus liagoroides (Yamada) Huisman, I.A. Abbott & A.R. Sherwood | Koshikijima | |

| Meristotheca coacta Okamura | Koshikijima | |

| Laurencia venusta Yamada | Koshikijima | |

| Pterothamnion polysporum (Itono) Athanasiadis & Kraft | Nagashima | |

| Kumamoto | Ulva conglobata Kjellman | Amakusa**, Goto-retto** |

| Codium contractum Kjellman | Amakusa | |

| Codium saccatum Okamura | Amakusa-shimoshima (Futae) | |

| Pyropia dentata (Kjellman) N. Kikuchi & Miyata | Amakusa | |

| Eucheeuma amakusaense Okamura | Amakusa-shimoshima (Ushibuka) | |

| Nagasaki | Pyropia suborbiculata (Kjellman) J.E. Sutherland, H.G. Choi, M.S. Hwang & W.A. Nelson | Goto-retto |

| Solieria dichotoma Yoshida | Fukuejima (Dozaki) | |

| Shimane | Goniotrichopsis reniformis (Kajimura) N. Kikuchi | Oki (Tsuto in Dogo) |

| Scinaia okiensis Kajimura | Oki | |

| Scinaia pseudomoniliformis Kajimura | Oki | |

| Scinaia tokidaea Kajimura | Oki | |

| Dudresnaya okiensis Kajimura | Oki | |

| Predaea bisporifera Kajimura | Oki | |

| Predaea tokidae Kajimura | Oki | |

| Aglaothamnion okiense Kajimura | Oki | |

| Dasysiphonia okiensis Kajimura | Oki | |

| Griffithsia okiensis Kajimura | Oki | |

| Plumariella minima Kajimura | Oki | |

| Antithamnion okiense Kajimura | Oki (Tsuto in Dogo) | |

| Niigata | Leathesia sadoensis Inagaki | Sado (Tassha) |

| Sargassum araii Yoshida | Sado (Inakujira) | |

| Porphyra palleola Noda | Sado | |

| Wrangelia tenuis Noda | Sado | |

| Callithamnion japonicum Noda | Sado | |

| Callithamnion nipponicum Noda | Sado | |

| Dasya minor Noda | Sado (Tassha) | |

| Hokkaido | Cladophora opaca Sakai | Kamomejima |

| Benzaitenia yenoshimensis Yendo | Yagishiri | |

| Agarum clathratum f. yakishiriense (Y.Yamada) I.Yamada | Yagishiri | |

| Hideophyllum yezoense (Yamada & Tokida) Zinova | Okushiri | |

| Griffithsia heteroclada Yamada & Y. Hasegawa | Okushiri |

Kyushu

Although algal floristic data in modern context have not been synthesized yet in Kyushu (Fig. 2), southwestern Kyushu (Kagoshima and Kumamoto Prefectures, Suppl. Fig. S2) is the transitional zone between warm temperate and subtropic (Okamura 1926, Chihara 1975). Seikai National Fisheries Research Institute (1981) synthesized the data of on-board and line-transect surveys of algal beds on the western coasts of Kyushu including islands. This report and NCB and MPCJ (1994) are the most comprehensive data of algal vegetation.

Kagoshima

Kagoshima Pref. include 9 populated western islands from Shimo-koshikijima to Shishijima; 4 islands are bridged to mainland and the 3 islands (Koshikijima-retto) between islands (Suppl. Table S1). In the prefectural algal flora (Shinmura 1990), species was shown in a table divided into 11 columns of districts including Koshikijima-retto. Five algae were described as new species from the prefectural western islands (Table 3).

At the southern most nonpopulated islands, Uji-gunto and Kusagaki islands, Tanaka (1956) collected tropical species including Chondria ryukyuensis and Nereia intricata. A unique macroalgal vegetation including Sargassum spp. was reported from a salty lake close to the coast of Kami-koshikishima (Shimabukuro et al. 2015), while algal beds were lost around the islands. Terada et al. (2021) monitored canopy forming species in Nagashima and the nearby three islands Ikarajima, Shourajima and Shishijima; the southernmost kelp Ecklonia radiata was recently disappeared in Nagashima, which is one of monitoring sites of algal beds selected by Ministry of the Environment (Terada et al. 2021). Ogawa (2001) introduced edible algae in Koshikijima: M. japonica, Sargassum fusiforme and subtropical components such as Eucheuma amakusaense and Digenea simplex (used as intestinal worm treatment) (Table 2). In FMDP, removal of sea urchins and transplantation are challenged in Nagashima (Table 5).

Kumamoto

In Kumamoto Pref., 20 populated islands (Amakusa-shoto from Gesushima to Oyanojima; Tobasejima) are included; 16 islands are bridged to mainland of Kyushu or the nearest island (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. S2). From the prefectural islands, 5 algal species were described (Table 3), in which E. amakusaense was named after the local district Amakusa. In the first Japanese review on coralline algae, Segawa (1954) reported presence of a rhodolith bed (as Lithothamnium bank) at a depth of 10 m around Yushima and growth of Undaria pinnatifida on such rhodolith. Segawa and Ichiki (1959) studied algal flora at Aizu in Maeshima. Yoshida (1961) studied the species composition of Sargassum beds at Ushibuka at the southern end of amakusa-shimoshima. Kumamoto Pref. (1968) reported sea condition, seascape, fauna and algal flora and recorded the occurrence of herbivores in Amakusa-shimoshima and Goshonourajima. The report also noted the dramatic decrease of the tropical sea urchin Echinometra sp. and mass mortality of Siganus fuscescens during the unusual low temperature winter in 1962-63 in the area. Later, algal flora was studied at Tomioka in Amakusa-shimoshima (Titlyanov et al. 2019), suggesting the impacts of elevated seawater temperature by comparing with the early algal list (Yoshida 1961). The species diversity was increased by two times because of an introduction of subtropical red algae and widespread opportunistic green algae in spite of the disappearance of brown algae.

Table 3.

Algal resources (mainly used as human food) of selected western islands which were listed in local guide books.

| Japanese name | Species | Koshikijima | Amakusa | Tsushima | Oki | Hegurajima | Sado | Rishirito |

| Green algae | ||||||||

| (Aosa, aonori) | Ulva spp. | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| Miru | Codium fragile | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Fusaiwazuta | Caulerpa okamurae | 〇 | ||||||

| Surikogizuta | Caulerpa chemnitzia | 〇 | ||||||

| Red algae | ||||||||

| (Iwanori) | Pyropia spp. | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇〇 | 〇 | |

| Makuri | Digenea simplex | 〇 | ||||||

| (Tengusa) | Gelidium elegans | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |

| (Funori) | Gloiopeptis spp. | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Shikinnori | Chondracanthus chamissoi | 〇 | ||||||

| Suginori | Chondracanthus tenellus | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Amakusa-kirinsai | Eucehuma amakusaensis | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Mirin | Solieria pacifica | 〇 | ||||||

| Tosakanori | Meristotheca japonica | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| (Tsunomata) | Chondrus spp. | 〇 | ||||||

| Ginnanso | Mazzaella japonica | 〇 | ||||||

| Egonori | Campylaephora hypnaeoides | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| Kyonohimo | Polyopes lancifolius | 〇 | ||||||

| Matsunori | Polyopes affinis | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Yuna | Chondria crassicaulis | 〇 | ||||||

| Brown algae | ||||||||

| Iroro | Ishige Sinicola | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| (Mozuku) | Nemacystus dicipiens etc. | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| Habanori | Petalonia binghamiae | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| (Kayamonori) | Scytosiphon spp. | 〇 | ||||||

| Tsurumo | Chorda asiatica | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Wakame | Undaria pinnatifida | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |

| Ao-wakame | U. peterseniana | 〇 | ||||||

| Tsuru-arame | Ecklonia cava ssp. stolonifera | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Arame | Eisenia bicyclis | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| Rishiri-kombu | S. japonica var. ochotensis | 〇 | ||||||

| Hondawara | Sargassum fulvellum | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Hijiki | Sargassum fusiforme | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Akamoku | Sargassum horneri | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Reference | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

In Amakusa-shoto, a group of 5 to 8 fishermen used to go diving to Iki, Tsushima and coastal waters of Korea to collect M. japonica or abalones by boat; the first Japanese diver’s eyeglasses were developed by two fishermen in Amakusa-shimojima in 1885 (Shindo 1975). In the area, 19 edible algal species (Amakusa Reg. HQ Div. Fish. 2014) are reported (Table 2). In the area, not only warm temperate but also subtropical algae such as Eucheuma amakusaensis are also decreasing.

In FMDP, removal of sea urchins, use of collected sea urchins as fertilizers for land crop, catch of herbivorous fishes, removal of competitive soft corals (Xenia sp.) and transplanting S. fusiforme for its intertidal bed restoration (Table 5). Soft corals are removed by covering with black sheet to cut light for photosynthesis of their symbiotic algae to enhance stock of M. japonica (Matsumoto 2017).

Table 4.

Distribution of destructive herbivores (sea urchins and fishes) in western islands of Japan

| Area | Sea urchin | Fish | ||||||

| Diadema spp. | Heliocidaris crassispina | Mesocentrotus nudus | Kyphosus bigibbus | Calotomus japonicus | Prionurus scalprum | Siganus fuscescens | ||

| SW Kyushu | ◎ | ◎ | ー | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | |

| NW Kyushu | ◎ | ◎ | ー | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | |

| SW Honshu | ◎ | ◎ | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ◎ | |

| NW Honshu | 〇 | ◎ | 〇 | ー | ー | 〇 | 〇 | |

| W Hokkaido | ー | ー | ◎ | ー | ー | ー | ー | |

Source: Fujita et al. (2006b, 2008), Fisheries Agency (2021)

Nagasaki

In Nagasaki Pref., 71 islands are populated; 53 islands from Saganoshima to Ikitsukijima face to East China Sea, while 18 islands from Takushima to Unishima facing to the Sea of Japan/East Sea (Suppl. Table S1, Suppl. Fig. S3, Suppl. Fig. S4, Suppl. Fig. S5, Kubo et al. 1981, Ito and Matsuoka 1993, Matsubayashi 1989). Thirty-six islands are isolated and the other islands are bridged to main land or nearest islands. The area from Cape Nomo in Nagasaki Pref. to the northern end of Honshu (Tsugaru Strait) is warm temperate (Okamura 1926, Chihara 1975).

Ichiki (1958) reported Huismaniella ramellosa collected from a carapace of a sea turtle, which was caught in a set net on the west coast of Tsushima. Algal flora was reported from Hiradojima by Migita and Kambara (1961) and Tsushima (Chihara and Yoshizaki 1970). From the prefectural islands, 2 algal species were described (Table 3). The important algal resources in Tsushima (Shirota 1981) are M. japonica, Solieria pacifica, Gloiopeltis tenax (as glue), Ecklonia cava ssp. stolonifera, E. radicosa, Eisenia bicyclis, S. fusiforme and Undaria peterseniana (called Waniura-kombu, but recently synonymized to U. pinnatifida by Uwai et al. (2023) (Table 2).

In Tsushima, Sargassum and Ecklonia species were collected by fishermen and stocked in ‘Mogoya’ (algal hut) after drying to use as fertilizers, and woman diver in Jeju visited this island to collect U. pinnatifida by sailing on raft boats ‘Taewoo in Korean language’ (Innnami 2011). The memorandum of manure feeding (1778) in Tsushima includes oldest record of ‘poor collection of algae’ though the reason was not mentioned.

Nishigawa (1963) examined the tidal level of marine algal vegetation in some sites including Fukuejima, Kabahsima and Tsushima. Nagasaki Pref. (1971) reported algal flora in Shimayamajima, Saganoshima, Wakamatsujima and Fukuejima and neighboring small islands in the southern part of Goto-retto; rhodolith beds were reported as ‘coralline ball’ around Shimayamajima and Tatarajima. Nagasaki Pref. (1972, 1973) reported algal flora and vegetation of Iki and Tsushima, respectively. Nagasaki Pref. (1975) reported algal flora and vegetation in the northern parts of Goto-retto including Ojikajima, Ukujima, Hiradojima and neighboring small islands. Mine et al. (1994) reported habitat depth range (0-26 m, abundant in 8-20 m) of M. japonica and enumerated 40 coexistent algae as its competitors in Wakamatsujima.

In Nagasaki Pref., algal beds have been occasionally reduced; the first recorded years of reduction were 1873 in Gelidium bed, 1940 in Eisenia and 1954-57 in Sargassum bed (Seikai NFRI 1981). In those days, however, many algal beds recovered after abolition of coal mining or prohibition of collecting Sargassum spp. used for soil fertilizers. The urchin barren dominated by Diadema spp. or H. crassipina were known in many parts of Gotto-retto, Iki and Tsushima (Nagasaki. Pref. 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975). Kumamoto Pref. (1968) recorded mass mortality of herbivorous fishes S. fuscescens and Calotomus japonicus in Goto-retto in 1962-63 winter, and Watanabe (1971) recorded mass mortality of herbivorous fishes S. fuscescens, P. scalprum and C. japonica in Iki; both events were caused by extreme low temperature though no consequent algal response was mentioned.

Yotsui et al. (1986) conducted cross-transplantation of S. fusiforme at healthy and undergrowth sites to reveal the reason of under growth in the west coast of Tsushima. Yotsui and Maesako (1993) restored Eisenia beds in urchin barrens on the east coast of Tushima, which is the earliest hectare-scale (1.6 ha) removal of sea urchins in Japan. Yotsui et al. (1994) found the prevalence of urchin barren on the east coast of Tsushima by hearing to fishermen, and thought the inactive dive fishing comparing with the west coast might explain the situation. Hamada (1999) reported removal of sea urchins and transplantation of Ecklonia in Oshima (Saikai).

Kiriyama et al. (1999a, 2002) and Kiriyama (2001) reported loss of blades in E. bicyclis and Sargassum spp. on the exposed coasts of the prefecture including islands of Goto-retto, Hirado, Tsushima and Iki. Kiriyama et al. (1999b) and Kiriyama (2004, 2009) concluded that browsing by herbivorous fishes is the critical factor of the undergrowth as the result of cage experiment. In Matsushima, Dotsu et al. (2002) studied the effects of D. setosum grazing on Sargassum in small fenced blocks (4 m2). To prevent browsing by herbivorous fishes, Suzuki et al. (2009) demonstrated the extension of Ecklonia stands transplanted on plates to find the effects of net cage in Tushima, and Shibata et al. (2011) introduced tree-like protectors installed before supplying Sargassum embryos in Iki.

In these islands as well as Hiradojima, mass drifts of Sargassum horneri was coming ashore and stranded in 2015 (Kiriyama et al. 2016) and poor development of microscopic sporophytes in wild and cultured U. pinnatifida due to high water temperature was recorded for the first time in 30-40 years (Kiriyama et al. 2018).

In Ojikajima, Kiyomoto et al. (2013) reported decrease of abalone resources as the result of drastic decrease of macroalgal beds. Algal beds were monitored by town office stuffs (Kurosaki 2016 and removal or transplantation of sea urchins to algal beds for improving gonads (Kiyomoto et al. 2018, 2021). In Iki, Yatsuya et al. (2014a) reported seasonal changes in biomass and net production of Ecklonia population, and the deterioration process of Ecklonia and Eisenia beds due to high water temperature in summer (> 30°C) and the subsequent cascading effect by browsing of herbivorous fishes in autumn (Yatsuya et al. 2014b, see also Fisheries Agency 2021).

Fisheries Department of Nagasaki Prefecture (2018) revised the Nagasaki Prefectural Isoyake Taisaku Guideline (1st ver. In 2012) and included the results of monitoring or restoration in some islands (Kabashima, Oshima (Iki), Oshima (Saikai) and Ojika and deployment of algal bank for transplantation at 74 sites in the following islands: Ikizukishima, Ojikajima, Tsushima, Kabashima, Nakadori, Ukusjoma, Fukuejima, Takushima, Iki, Takashima, Narushima, Wakamatsujima, Oshima (Saikai), Hisakajima, Makishima and Oshima (Hirado).

Among 37 fishermen groups joining FMDP (Table 5), removal of sea urchins H. crassispina and/or Diadema spp. and enclosure with fence net to exclude herbivorous fishes are most common. Unique challenges are collection of K. bigibbus using cage traps developed in Fukuejima or gill nets on wave dissipating concrete blocks (shelter of the fish) along the breakwater of fishing ports in Iki (Kuwahara et al. 2015, Fisheries Agency 2021).

Saga

In Saga Pref., 9 islands are included; 7 islands are isolated and two island are bridged to the main land (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. S4). Takezakijima is in Ariake Sea in the south of the prefecture, while the other islands are facing to Sea of Japan/East Sea. Saga Pref. (1970) reported algal flora on some islands; Seikai National Fisheries Research Institute (1981) on Takezakijima and Iida and Maeda (1996) on Matsushima. Before these studies, Okamura (1910) stated that the most important algae were Gloiopeltis spp. and U. pinnatifida, followed by Gelidium elegans, Ulva spp. and Pyropia spp., and introduced his opinion to enhance these algal stocks. Ootsu and Kanamaru (2013) and Fujisaki (2017) reported the status and trend of algal beds. Genkai Fisheries Research and Development Center (2015) published a manual for algal bed restoration, explaining removal of sea urchins and the related techniques.

Fukuoka

In Fukuoka Pref., 10 populated islands from Himeshima to Umashima are included; only Shikanoshima is bridged to main land (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. S3). Algal flora was reported from Okinoshima, an unpopulated sacred island 60 km north of mainland (Higaki 1971) and Shikanoshima (Nakamura et al. 2012).

Akimoto et al. (2008b) compared the status of algal beds of all prefectural coasts with the previous data (1976-78) and detected reduction of Eisenia and Sargassum beds only at a depth of > 7m in Oshima. Akimoto et al. (2008a) reported on the distribution of Diadema spp. and the evaluated the algal recovery after removal of the sea urchins. Later, Hidaka et al. (2016) reported changes of dominant algal species or biomass and heavy browsing by herbivorous fishes on Eisenia, Ecklonia and Sargassum in Aishima, Oshima, Genkaijima, Shorojima and Himeshima.

Three groups of fishermen joined FMDP to remove sea urchins in the prefecture (Table 5). In Ainoshima, fishermen succeeded in enlargement of restored Sargassum beds by removing sea urchins at the upstream area of the coastal current in the south of island (See reference for Ainoshima in Table 5).

Table 5.

Fisheries Multiple functions Demonstration Projects conducted in western islands of Japan

Southwestern Honshu

Yamaguchi

In Yamaguchi Pref., 10 islands are included; 4 islands are bridged to main land of Honshu (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. 3). Some notable algae such as Halimeda discoidea were reported from a reef (16 m in depth at the shallowest ridge) near Mishima (Yoshida and Kakuda 1979). Kushimoto (2015) found Acetabularia calicurus in Tsunoshima and Futaoijima. No comprehensive floristic studies were reported from western islands of the prefecture. Algal vegetation on transects were recorded at Omijima (Yamaguchi Pref. 1981), Oshima (Murase et al. 2011) and Aishima (Murase et al. 2013).

In Futaoijima, relation between algal vegetation and herbivorous fish, primarily S. fuscescens, was intensively studied. Noda et al. (2002) revealed natural food of the adult-stage of this rabbitfish in autumn and spring, and Noda et al. (2011) reported diet and prey availability of this fish occurring in a Sargassum bed. Noda et al. (2014) studied on browsing of E. bicyclis and several sargassaceous species by S. fuscescens in relation to the differences in species composition of algal beds. In this prefecture, one group in Mutsurejima joined FMDP (Table 5) and succeeded in restoration of Eisenia beds by removal of sea urchins and transplanting Eisenia juveniles to the bottom.

Shimane

In Shimane Pref., 6 populated islands are included; 4 islands form Oki-shoto, and 2 islands, Daikonjima and Eshima, are located within the semi-closed lake Nakaumi and bridged to the main land (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. 3). Algal flora was intensively studied in Oki islands which is composed of 4 populated islands, Dogo, where marine biological station of Shimane University is located, Nishinoshima, Nakanoshima and Chiburijima. After the first report (Hagiwara et al. 1970), the flora was repeatedly revised by Kajimura and his colleagues (Hirose and Kajimura 1973, Kajimura 1975a, 1975b). Although he described 12 currently accepted species (Table 3) and added 14 notes on the flora (e.g., Kajimura 1997), comprehensive algal list has not been published yet. He collected deep-water algae using a dredge, and revealed a profile of deep-water flora down to 60 m in depth (Kajimura 1987). The algal flora of Oki-shoto includes interesting species such as Caulerpa scalpelliformis (Kajimura 1969, 1981a) whose habitats in the islands were designated as a national natural monument in 1922 because of its isolated distribution apart from the type locality in the Red Sea (Agency for Cultural Affairs 2023), and the deep-water kelp Streptophyllopsis kuroshioensis (Kajimura 1981b). Rural Culture Association Japan (1991) enumerated some traditionally consumed algae, including Chondrus crassicaulis (strong accent). In the inland brackish water sea, Nakaumi, Miyamoto and Kunii (2006) recorded 14 species of low salinity-tolerant algae on the 15 sites including Daikonjima and Eshima.

Oki Fisheries High School (2010) surveyed the distribution and type of algal beds and barren areas around Dogo. Yoshida (2016) overviewed the algal bed status and rocky-shore denudation along the coast of Shimane Prefecture including Oki-shoto and detected deforested areas in Dogo and Chiburijima by hearing from fishermen. The deforestation is less common on Oki-shoto than in southwestern islands mentioned above. Oki Fisheries High School (2010) challenged algal bed restoration by installing small set nets to remove herbivorous fishes, by removing sea urchins and gastropods using a suction pump and by transplantation of S. horneri juveniles on stones. In Oki, a unique columnar reef was developed to construct larger kelp forests on sandy bottoms and monitored for 22 years, and suggested requirements for installation (Hosozawa et al. 2019).

Northwestern Honshu

Ishikawa

Ishikawa Pref. includes one bridged island, Notojima, in Nanao Bay, south of Noto Peninsula and one isolated island, Hegurajima, in the north of the peninsula (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. 4). Algal flora of Notojima was reported by Imahori (1955a, 1955b, 1955c) and Tajima (1982). Around the island, A. cayculus (Suppl. Fig. S6) has been known since Ichimura and Yasuda (1926) the ecology was studied by Sano et al. (1981), and ‘mozuku’ (Nemacystus decipiens (Suringar) Kuckuck) entangled on Sargassum species has been collected by fishermen (Tajima 1982). Hegurajima is known as an island of ‘Ama’ (woman-diver) who collects abalones, turban shells and macroalgae (Hokkoku Sinbunsya 2010). Algal flora of the island was reported by Ichimura and Yasuda (1940). Results of subtidal line transect survey on the southeast coast (Fujita et al. 2006a) and intertidal algal flora (Sakai et al. 2009) were reported, but comprehensive algal list has not been made yet. Many algae including E. cava ssp. stolonifera were collected, eaten by local residents and sold at a morning market in Wajima City for souvenirs (Hokkoku Sinbunsya 2010).

Toyama

There are no populated islands in the prefecture but algal flora and vegetation were studied in non-populated isolated small island: Abugashima (Fujita et al. 2003, Terawaki and Arai 2008) in the western side of Toyama Bay (Fig. 4). Around Abugashima, mass mortality of the northern species of sea urchin Mesocentrotus nudus was recorded at a depth of 12 m at unusual high temperature (30°C) in 1994 (Fujita et al. 2008). Marine algae recolonized the barren bottom after the mass mortality event, but not remained because of sedimentation.

Niigata

Niigata Pref. includes Sado and Awashima (Fig. 4); Sado is the largest among the islands in the western islands (Suppl. Table S1), around which algal bed area was 7306 ha (NCB and MPCJ 1994). Algal flora of Sado and Awashima (and Tobishima in Yamagata Pref.) were preliminarily reported by Hirohashi (1937). Mitsuzo Noda (1909-1995) studied algal flora of Sado in detail and described many new species (Noda 1960, 1963, 1973, 1974, 1987, Honma and Kitami 1978, See also papers cited in Noda (1987)), among which 6 species are currently accepted taxonomically (Table 3). This island might be a hot spot of algal diversity, but many species he established has synonymized into the related taxa (Suzuki 2024); the remaining species are waiting for verification using molecular techniques. Nagumo et al. (2000) demonstrated color pictures of marine algae as well as seagrass and diatoms. In addition, Kawai et al. (2000) described a new species Chorda rigida from the main land of Niigata Pref., which was also found in Sado and Awashima.

Noda and Kitami (1962) reported on local product of E. cava ssp. stolonifera, as ‘brick-arame’ in Sado. Hamaguchi (1999) introduced edible marine algae (Table 2). Among them, ‘igoneri’, a gel made from Campylaephora hypnaeoides is a soul food of the residents in Sado though its food culture originated from Fukuoka and is also common on the western coast of Honshu.

Ohkubo studied the relation between distribution of Sphaerotrichia divaricata and Sargassum spp. and stability of bottom characters on the southeast coast of Sado (Taniguchi and Ohkubo 1975). Terawaki and Arai (2002) paid attention to an algal vegetation of the transitional zone between rocky and sandy bottom and examined the hardness of rocks, thickness of sand and tensile strength of dominant bed-forming algae in Mano Bay of Sado. Terawaki and Arai (2007a) compared agal vegetation between natural and artificial reefs on the southeastern exposed coast.

Ishikawa (1993) conducted a total of 21 line transects in Sado, Awashima and main land and detected barren state in the southwestern coast of Sado and western coast of Awashima. Ishikawa and Yoshida (2010) reported the distribution and flora of Sargassum beds in Mano Bay, and Ishikawa and Yoshida (2010) clarified the factor of maintenance of barren area offshore of the beds. Hamaoka (2020) compared accuracy rates among various methods of macroalgal beds discrimination via aerial photos taken in Mano Bay.

In Awashima, Noda (1970) reported 189 species of marine algae. Yamakawa and Hayashi (2004) revealed relation between food habits of the turban shell and algal distribution on the island. Terawaki and Arai (2004, 2007b, 2009) reported algal vegetation on the north, west and southeast coasts of the island, and on breakwater on the east coast, respectively. Yamakawa and Hayashi (2004) reported on the relation between food habits of the horned turban shell, Turbo cornutus and algal distribution. Kitano et al. (2007) intended to develop a habitat suitability index model for algal beds at the island. Yoshida and Uchida (2015) synthesized information on isoyake (=deforested) areas in Awashima and Sado. Hamaoka (2022) recently collected data of algal bed area in Awashima using drone data. He also found that the factor preventing recovery of algal beds in the island was grazing by snails.

Yamagata Pref.

Tobishima is the only one populated island in Yamagata Pref. (Suppl. Table S1). In the island, Hoshina et al. (1997) and Hoshina and Hara (1999) reported the latest algal flora down to 20 m in depth after the following earlier reports: Hirohashi (1947), Kanamori (1965, 1971) and Noda and Saito 1970). Interestingly, growth of cold temperate species Neodilsea yendoana Tokida was solely reported from Tobishima among the islands of northwestern Honshu.

Western Hokkaido

In the western coast of Hokkaido., 6 populated islands are included; 5 of the islands are isolated, while Kamomejima is connected to main land by sandbar (Suppl. Table S1, Fig. 5) All of the coasts of Hokkaido are cold temperate, represented by kelp in the genus of Saccharina though the western coast is washed by TWC, which runs northward after branching Tsugaru Warm Current running through Tsugaru Strait (Yasui et al. 2022). In Hokkaido, comprehensive algal flora has not been published; algal vegetation was studied in 23 points with special reference to the vertical distribution, including Oshima-kojima, Yagishirito, Rishirito and Rebunto (Yamada 1980). Algal and sea grass beds on the western coast of Hokkaido is known as a spawning field of the herring Clupea pallasii (Hoshikawa et al. 2002). Though the spawning of the fish has been lost for a century in southwestern Hokkaido and reduced in northwestern Hokkaido, the fish is increasing in the decade; even ‘whitening of the sea surface’ (due to ejaculation by male fishes during spawning) was observed at Kamomejima (Suppl. Fig. S6) in the winters of 2020 and 2023 (Nakao 2023).

At Oshima-kojima, the southernmost non-populated island of Hokkaido, algal flora was studied by several authors since 1940’s (Yamada 1942, Kinoshita and Shibuya 1946, Hasegawa 1951, Noda and Yokoyama 1971, Sanbonsuga 1987) and showed that the island is the Ecklonia-Saccharina transition zone and presence of some warm temperate species such as U. peterseniana and species in the genera Padina, Dictyopteris and Peyssonnelia, particularly in deeper waters (20 to 50 m in depth). On the contrary, warm temperate components have not been found in nearby larger non-populated island, Oshima-oshima (Saito et al. 1969) though detailed studies have not been conducted. The other populated islands are isolate and cold temperate (Okamura 1926, Chihara 1975, Yoshizaki and Tanaka 1986). Algal flora was studied in all of the islands as follows.

In Okushiri, Hasegawa (1949, 1950) made a list of marine algae (including northernmost record of Caulerpa okamurae) and described a red alga Griffithsia heteroclada. Later, Abe (1997) updated the algal flora in the island. Kakizaki (2000) reported the algal growth on the bedrock submerged due to the 1993 southwest-off Hokkaido Earthquake and use of the area as sea urchin fishery grounds by feeding cultured kelp. Algal flora of an island connected to main land by sandbar, Kamomejima (Fujita and Tsuda 1987) also includes warm temperate components such as Sargassum fusiforme and Helminthocladia yendoana. At that time, urchin barren dominated by M. nudus was limited, but enlarged recently (unpublished data).

In the northwestern Hokkaido, Yendo (1911) reported the geography and distribution of useful algae of 4 islands, Teurito, Yagishirito, Rishirito and Rebunto and the main land coast. I. Yamada (1966) studied a deep-water kelp Agarum clathratum subsp. yakishiriense (as A. yakishiriense) growing at a depth of > 7 m in Yagishirito. In Teurito and Yagishirito, Hokkaido (1979) made a list of marine algae for the preparation of large-scale abalone habitat formation. In addition, Tomita et al. (1978) reported the biota on the inlet along the northeastern coast of Teurito. Kizaki (1989) reported the civil activity of land afforestation to store enriched soil (source of nutrients for marine algae) in Teurito because early colonizers of the neighboring island Yagishirito cut trees to build their houses or to make firewood in early 19th century.

From Oshima-kojima to these two islands, Saccharina japonica var. religiosa is the dominant annual kelp while it is replaced by a commercially more important biennal species S. japonica var. ochotensis in Rishirito and Rebunto (Miyabe 1957). Fukuhara (1969) recorded unusual mass stranding of non-native (Russian) kelp Alaria fistulosa in wide area of the western coast of Hokkaido, including Rishirito and Rebunto.

Kaneko and Niihara (1970) reported algal flora in Rishirito after Kinoshita and Sakuma (1933). Algal flora and phenology in Rishirito and Rebunto were studied by Kurogi (1971) to find indicator species to predict the good or bad crop of S. japonica var. ochotensis. Later, Kawai et al. (2007) added some species to algal flora of Rishirito. In Rebunto, after the small report on warm temperate algae found in Todojima Inlet (northernmost rocks north of Rebunto) (Fukuhara 1959), Hokkaido (1980) reported algal flora in Rebunto. Sato (1997) and Nishiya (2010) recorded the harvest and use of some useful algae (Table 3).

In Rishirito and Rebunto, cold temperate species such as Odonthalia corymbifera and Silvetia babingtonii were reported by the above authors. These are the only islands among the western islands where floating ice comes ashore in episodic cold year such as 1984; the kelp as well as sea urchins were damaged by the ice (Kasahara 1984). In addition, Matsunaga and Yamada (1974) reported occurrence of Microzonia abyssicola (as Syringoderma australe, see AlgaeBase for details) in Rishirito as the only one habitat of Syringodermatales in Asia. Nabata et al. (1981) studied ecology on Sargassum confusum.Nabata (1985) suggested the northward extension of a warm temperate species Sargassum siliquastrum from Okushirito to Teurito, Yagishirito and Rishirito, which was presumably accompanied by the transplanted wild abalone juveniles.

Kawai et al. (2016) studied the spatial distribution of Sargassum siliquastrum and S. boreale (potential competitors of S. japonica var. ochotensis) in Rishirito and Rebunto, and suggested that elevation of sea surface temperature in August and changes of TWC paths in the northern area might have affect their horizontal and vertical distribution.

In Rishirito and Rebunto, to enhance wild stock of S. japonica var. ochotensis as well as the closely related herbivores (abalone and sea urchins), a variety of efforts have been done by fishermen. Removal of sea urchins (primarily M. nudus) subsidized by the local fisheries cooperative was conducted to reduce feeding damage on the kelp in 1932 (Kinoshita 1933). This is the earliest record of sea urchin removal in Japan. In addition, ‘chain-swinging method’ was devised in Rishirito (Nabata and Matsuda 1983). By floating a unique apparatus (lumber or FRP float) with drooping chains which can abrase the sea bottom, competitive weedy algae were removed using wave energy though the apparatus should be moved to other sites by hand after clearing a site (Nabata and Matsuda 1983). As the occasional reduction of S. japonica var. ochotensis causes economic damages, Nabata et al. (2003) examined relatioan between the kelp production and water temperatures and concluded that reduction of kelp was due to elevated water temperature in winter and the consequent increased grazing on young kelp sporophytes by sea urchins and snails. Another commercial kelp was Saccharina cichorioides (Suppl. Fig. S6), which was collected (stranded materials) and ground to powders for cooking in Yagishirito, but the kelp is not collected now because of its low resource level.

In FMDP (Table 5), one group in Okushirito controls (transplants) sea urchin M. nudus and introduced seeded kelp to restore the beds, while groups in Rishirito remove competitive algae by chain-swinging and/or culling sea urchins. As M. nudus is the high-priced species, transplanting to rich algal beds is preferred to crash in the sea.

Conclusion

In this review, multifaceted information of macroalgae in western islands (primarily populated islands) of Japan was agreed for the first time. Algal flora has been studied in most islands in northern Honshu and Hokkaido but limited to major islands in Kyushu. Therefore, floristic survey should be promoted in the unveiled islands and should be repeated to know the temporal changes in other islands.

Up to now, 36 species were described on the specimen collected from these islands (Table 3). In spite of many reports and described species, most algae have not been identified with genetic information in moder context, waiting for re-identification with molecular techniques. For example, Akita et al. (2020) concluded that a non-stoloniferous undulate kelp from the western islands which had been identified as E. kurome should be included in the dominant kelp E. cava var. stolonifera using multigene molecular phylogeny of mitochondrial atp8–16S rDNA, cox1 and cox3, plastid atpB, psaA, psbA and rbcL gene sequences, and nuclear microsatellite marker. Yang et al. (2021) demonstrated the presence of three and two undescribed red algal taxa of the genus Gloiopeltis using the mitochodrial 5′ end of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI-5) in Nakadorijima and Iki in Kyushu, respectively.

The update of algal flora is supposed to contribute to accurate understanding of algal diversity in each island. In addition, exploring unveiled islands may increase the chance to find any new species or varieties in taxonomy, and more ‘refuges’ in deforested region in ecology. Actually, some species from these islands are listed as endangered or near threatened species in the red data book (Ministry of the Environment 2020); Acetabularia caliculus is an endangered species, and Caulerpa scalpelliformis, Eucheuma amakusaense, Meristotheca japonica and Saccharina cichorioides are near threatened species.

Algal vegetation has been studied primarily using line transects after introduction of SCUBA diving and recently by using drone (Fujita et al. 2010, Fisheries Agency 2021). Besides, Hasegawa (1951) and Kajimura (1987) unveiled deep-water algal community in Oki-shoto using repeated collection with drooped rakes. Some locality is selected as national monitoring sites (e.g., Nagashima). In order to monitor the status and range of algal beds, periodical and large-scale survey is needed by introducing drones as shown in Sado (Hamaoka 2020) and Awashima (Hamaoka 2022); introduction of underwater drone is also needed to visualize the inaccessible algal communities to confirm attachment on substrata (in other words, not the alien drifts), particularly in deep-water sites such as Oki-shoto and Oshima-kojima.

In western islands, a variety of algal bed restoration have been originally challenged by fishermen. Removal of sea urchins (now extending all over the country) started in Rishirito and developed in Tsushima. Removal of herbivorous fishes with cage trap and gill-net covering on concrete blocks were developed in Fukuejima and Iki, respectively. Removal of competitive algae by chain-swinging (Rishirito) and removal of competitive soft corals (amakusa-shimoshima) are practical. Although these activities are financially subsidized in the national support systems, depopulation (see Suppl. Table S1) and aging of local fishermen and the related stakeholders as well as traffic inconvenience (decrease of ferry service) for external supporters, namely, short of actual workers are most serious. In addition, repeated damage by elevation of water temperatures and related phenomena (e.g., intensification of storm, grazing and oligotrophication) have made it difficult to maintain or restore algal beds. On the contrary, isolated islands can be an affordable unit to protect algal beds, less connected with the neighboring algal bed assemblages as shown in the case of removal of herbivorous fishes in Iki. This situation is beneficial for the algal beds to prevent from continuous invasion of herbivorous fishes.

Particularly, in case of exposed coasts of islands, shore as well as ports have been protected from erosion by extended breakwater and increased concrete blocks, but these have provided habitats or shelters for herbivores. We should also watch over these structures and control the inhabited herbivores. The islands are the ‘forefronts’ to conserve domestic algal beds.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at Jeju Journal of Island Science website (https://www.jjis.or.kr/).

- jjis_01_01_04_Supplement_Table_S1.pdf

Supplementary Table S1. Profile of western Islands, Japan, ordered from south to north

- jjis_01_01_04_Supplement_Figure_S2.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S2. Map showing location of all populated islands in Kagoshima and Kumamoto Prefectures in western Kyushu.

- jjis_01_01_04_Supplement_Figure_S3.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S3. Map showing location of all populated islands in south to middle Nagasaki Prefecture in western Kyushu.

- jjis_01_01_04_Supplement_Figure_S4.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S4. Map showing location of all populated islands in north Nagasaki, Saga and Fukuoka Prefectures in western Kyushu. See S5 for details in Tsushima and Iki.

- jjis_01_01_04_Supplement_Figure_S5.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S5. Map showing location of all populated islands in Tsushima and Iki in Nagasaki Prefecture.

- jjis_01_01_04_Supplement_Figure_S6.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S6. Characteristic marine algae, polar reef and agar-like product ‘igoneri’ in western islands, Japan. 1: Eucheuma amakusaense inhabiting Amakusa-shomojima (photo by Hikaru Tomikawa, Hikaru). 2: Caulerpa scalpelliformis collected from Nakanoshima,. 3: Streptophyllopsis kuroshioensis collected from Dogo, 4. Polar reefs on which Ecklonia cava var. stolonifera grows at Dogo. 5. Acetabularia caliculus collected from Notojima, 6. Campylaephora hypnaeoides collected from Sado. 7. Agar-like gel called ‘igoneri’ made from C. hypnaeoides. 8. The whitened sea surface due to releasing sperms by herring at Kamomejima (photo by Takaaki Aosaka) and the eggs spawned on marine algae (inlet). 9. Saccharina cichorioides from which kelp powder was is made at Yagishirito.